Find new heights of adventure this fall – explore the Potomac region’s best outdoor climbing spots!

/Contemporary rock climbing was shaped by both the landscape of the Potomac River region and the people who dared to scale its cliffs

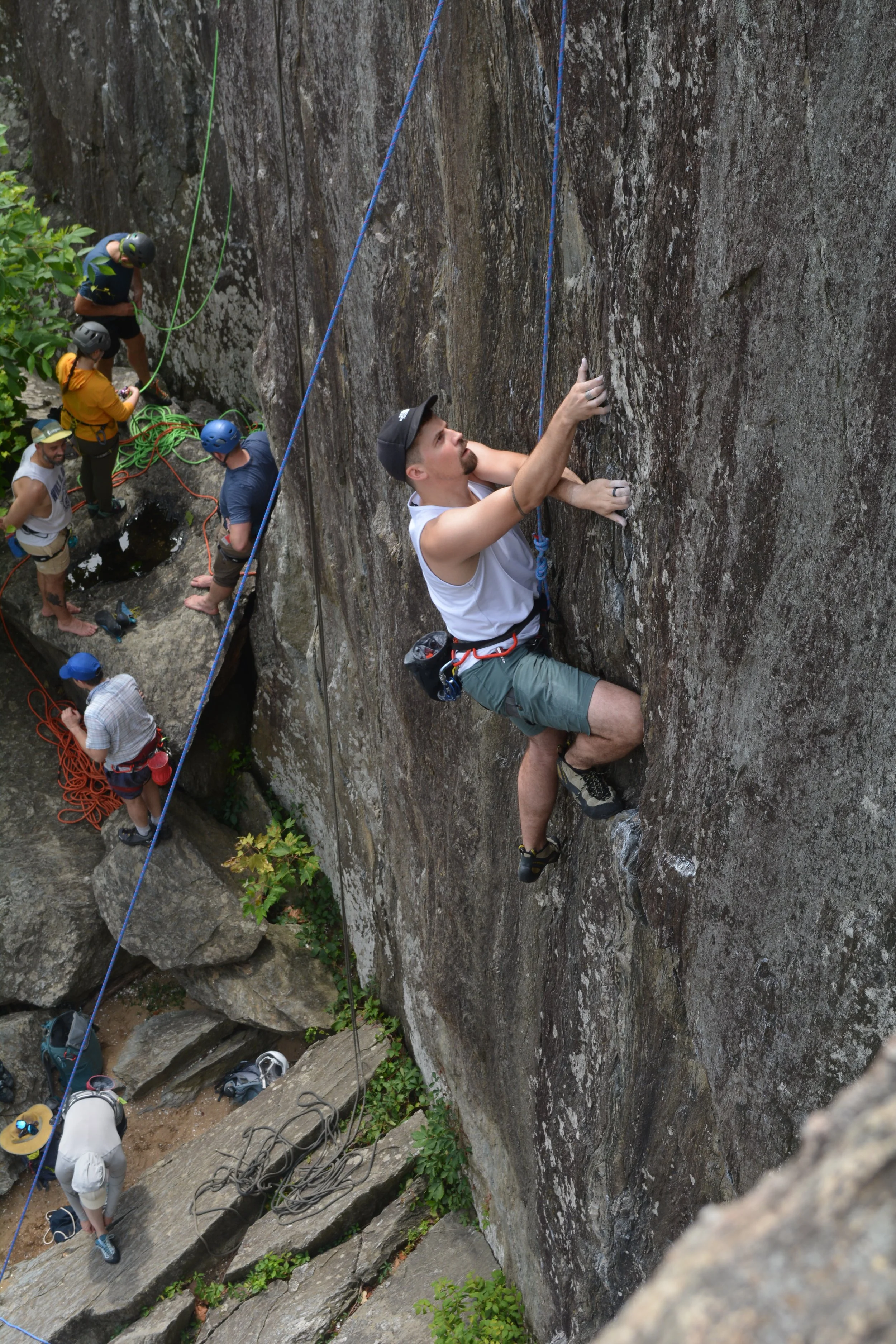

climbing Gunsight to South Peak at Seneca Rocks taken by Brett Kelly

When most people think of rock climbing, they think of the soaring steep buttress of El Capitan in the Yosemite Valley, but the Potomac River has been a cradle of American climbing for over a century. The same processes of erosion and geologic features that formed the dramatic rapids of Great Falls have left behind steep schist cliffs on the Maryland and Virginia banks from Great Falls through the Mather Gorge to the Carderock Recreation Area.

Prolific early climbers like Herb and Jan Conn, Paul Bradt, Don Hubbard, and Gus Gambs, who began climbing in this area, not only went on to record many notable first ascents throughout the United States, but made major contributions to the development of American rock climbing culture and technique in its pre-WWII infancy.

CLimbing at Great Falls, VA

Getting started on the banks of the lower Potomac

Beginner climbers can still find a vibrant climbing network in the Potomac region, recreating at these same cliffs. “In this area these include the Potomac Mountain Club (PMC) and the American Alpine Club (AAC), both of which offer climbing events and local trips,” shared Simon Carr of the PMC. To get the most out of the opportunities offered by climbing clubs, beginners should be on the lookout for “gym to crag” classes offered by their local climbing gym. Those looking to develop skills to be more self-sufficient may also be interested in taking an anchor building class from a local gym to safely set up their own ropes for climbing. “The [Potomac Mountain Club] also offers instructional classes run by experienced members,” Carr said.

As for the best crags for beginner climbers to take advantage of, Carr said, “there is good quality top rope climbing available at Carderock and Great Falls on the banks of the Potomac River, which allows newer climbers the opportunity to develop climbing skills...North of Washington, DC is Sugarloaf, a private preserve just north of Germantown that allows toprope and moderate trad climbing. The Potomac Mountain Club has frequent trips to this location.”

Seneca Rocks, climbing near the upper Potomac

belaying another climber at Seneca Rocks. Photo taken by Connor Wilczek

Climbers looking for a more adventurous setting may want to travel to its headwaters in West Virginia. Above a small fork of the Potomac towers an unlikely fin of quartzite, Seneca Rocks. The climbing at Seneca Rocks is often steep and exposed due the blocky nature of the rock and the thin summit ridge, which measures only a few feet across in places.

Many of the easier routes are approachable for climbers who are still developing their climbing technique and strength, while offering a wild sense of adventure. Carr characterized it as “a large, potentially serious cliff,” emphasizing that, “newer climbers may want to hire a guide, take an instruction course, or partner up with more experienced climbers before visiting that crag.” Seneca Rocks Mountain Guides can introduce newcomers to the complex climbing environment at Seneca Rocks and offer instruction in all manner of climbing skills.

During WWII, Seneca Rocks was the major training ground in rockcraft for the Army 10th Mountain Division. The Mountain Division would ultimately become a watershed for mountain sports in the United States, as skills and equipment developed during the war dispersed into civilian life afterwards.

While many experienced mountaineers from the Mountain West and West Coast contributed their knowledge to the Mountain Division, local climbers like Bradt & Hubbard established the climbing scene that Army newcomers met at Seneca Rocks. The Mountain Division’s training at Seneca Rocks enabled them to confront Italian and German forces on the mountain ridges of the Apennines that the Axis forces assumed the Allies couldn’t possibly climb.

Conserving the land climbers love

Climbers have a long history of promoting conservationism. In the Potomac region, climbers have maintained an ethic of climbing using “traditional” methods, and have avoided altering rock faces by installing bolts. This allows today’s climber to have a similar experience to those climbers who established the routes, approaching a cliff face with little sign of human passage.

With the explosion in popularity of outdoor recreation, the largest threats to climbing in the Potomac region today are our own impact. Given the strain many of our parks are experiencing due to cut staff and funding, as well as the current government shutdown, our impact is more significant than ever.

Carr mentioned, “Climbers can still access the climbing areas but the shutdown has left the trails more vulnerable to trash and bathrooms un-serviced…[climbers] should learn and practice Leave No Trace principles…’pack it in, pack it out’.” Leave No Trace (LNT) principles include following established trails to avoid contributing to erosion and de-vegetation.

Climbers in particular should take care of trees that we use for anchoring ropes by padding them to protect them against rope abrasion or find more durable anchor alternatives like using rock features. And we should avoid polluting our environment with litter and noise. Part of the wild character of the spaces we inhabit is that we share it with many species who can’t tolerate our trash, loud music, or the stress of dogs passing through their habitats.

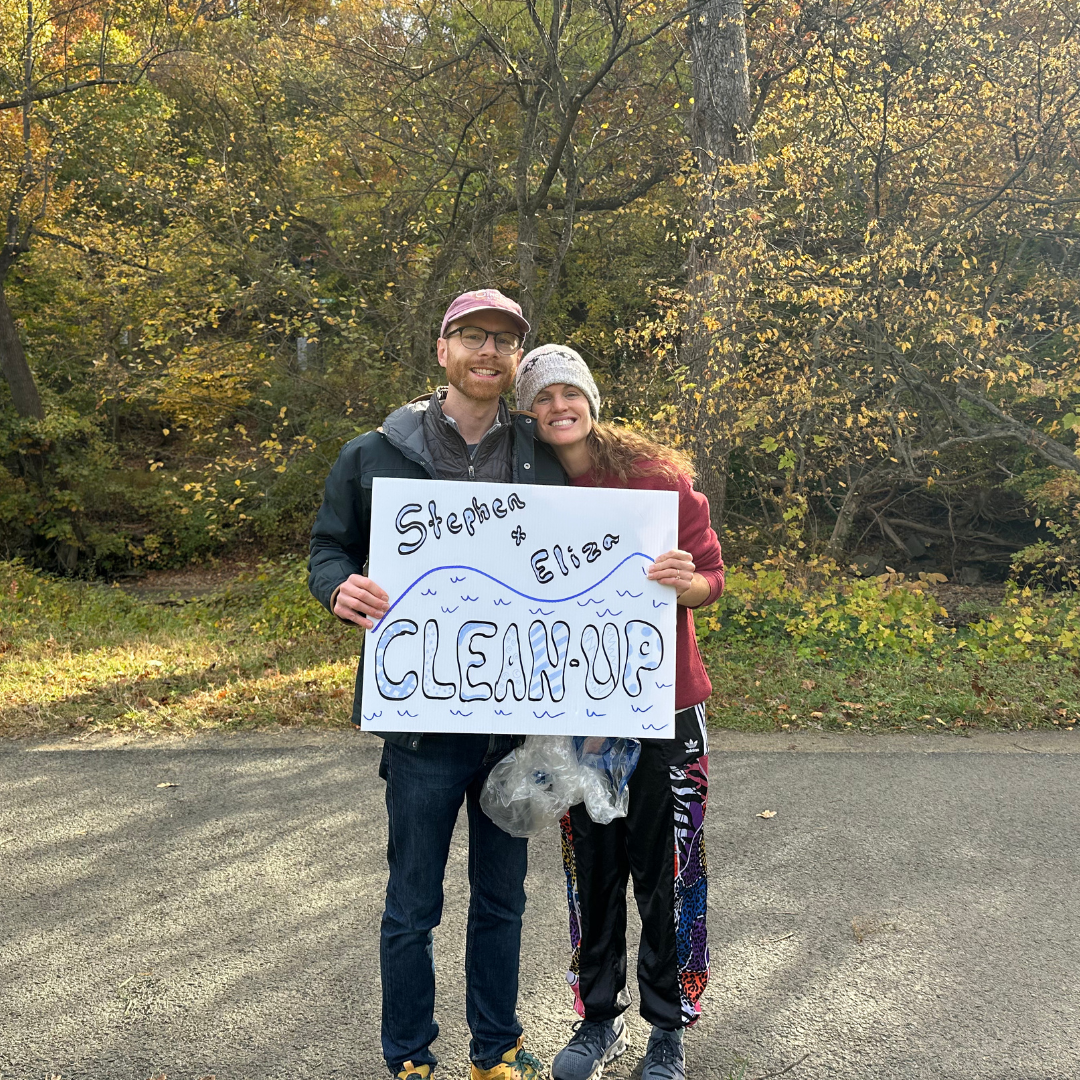

Jackson Moody of Mid Atlantic Climbers (MAC) emphasized the importance of stewardship: “MAC has put in a lot of work with county parks and National Parks around the region where much of our climbing lies. We have been involved with the development of several climbing management plans and we hold regular stewardship events at these areas. Holding these events is a great way to show land managers we care about the natural resources and are happy to lend a hand!

Many of our stewardship events are focused around picking up trash, building sustainable trails that reduce erosion, or pulling invasive species. All of these things directly improve the area we are working in but they all also have positive downstream impacts for the entire watershed.” Climbers can also offer unique skills to clean up areas that others can’t. “We held one event last year [at Catoctin Mountain Park] where we built natural anchors and rappelled down rock faces and into large cracks to pick up trash that was otherwise inaccessible. It was a really cool event and we’d love to do more like it in the future!”