Indigenous Voices: Discover the hidden beauty of Nanjemoy Creek

/How the Piscataway people are still protecting this pristine Potomac River place

photo courtesy of gabrielle tayac

Dr. Gabrielle Tayac

Member of the Piscataway Indian Nation and activist Indigenous scholar

I named my daughter, Jansikwe, meaning “Beautiful River Woman” to honor ancestral indigenous connections to the Potomac River. As Piscataway people, our identity merges entirely with the riverine environment and adapts to its changes. Piscataway translates to “where the waters blend.”

Like the tides, wherever I may go into the wide world, I always return to the Potomac.

I have devoted a significant part of my life working to recover our history, protect our sacred sites, and educate a wider public about Native American experiences. Now in my 50s, I am allowing myself more time to immerse myself in the restorative beauty found in a place, like our tribe, largely unknown: Nanjemoy.

A pristine creek with restorative powers

For now, I have settled onto the deeper, gentle side, caring for the home of an elder artist. Here awareness becomes so harmonious with interconnected natural beings that I can hear eagle wings flapping.

The night sky still unpolluted, the milky way appears. Jumping fish splash loudly. And I have not seen one piece of human made trash float by the dock. All seems in alignment. The large contiguous forest breathes, a massive blue heron rookery within it, only about 50 miles south of Washington, D.C.

Nanjemoy Creek presents as a river itself, thirteen miles long, it flows into the Potomac in Charles County, Maryland. In pre-European times, fertile soil, abundant clay, game, fish, old growth forests, and wild plant foods nurtured human communities for millennia. Nanjemoy always has maintained a remote, natural character, and still readily receives returning presences of nearly lost wildlife.

History of the Piscataway people

The Piscataway once were organized as a chiefdom, a network of interdependent sub-tribes that recognized a central leader titled the Tayac. The Nanjemoy, one of the chiefdom sub-tribes, appeared on Captain John Smith’s 1608 map. Each sub-tribe stewarded an area usually based around the Potomac’s tributaries. In a sense, the chiefdom’s government patterned itself on the convergence of smaller waterways which then combined to gain the force, power, and resources that we find in the Potomac’s energy as it surges into the Chesapeake Bay.

English colonization arrived with the Ark and the Dove in 1634. Settler encroachment brought disease, removal, and reservations.

War with colonies as well as other tribes resulted in massive losses. The Nanjemoy tribe struggled to stay in their homes as long as they could, eventually forced to retreat further to a restricted area. Many survivors either eventually migrated north while some moved together into local places where they could find the protection.

The Nanjemoy lost its Native majority by the late 17th century, witnessed the brutality of slavery, and declined in biodiversity. We became nearly invisible in our own homeland although strands of culture always endured.

Piscataway people like my grandfather, Chief Turkey Tayac, spent much time collecting herbal medicines, wild foods, and seeking remnants through archeological explorations with his best friend, Calvert Posey. Tribal families have always lived in the area as well, although largely pushed back from the prime waterways.

Governor O’Malley finally restored our tribal status in Maryland in 2012 after an intergenerational effort spanning decades.

Taking care of each other

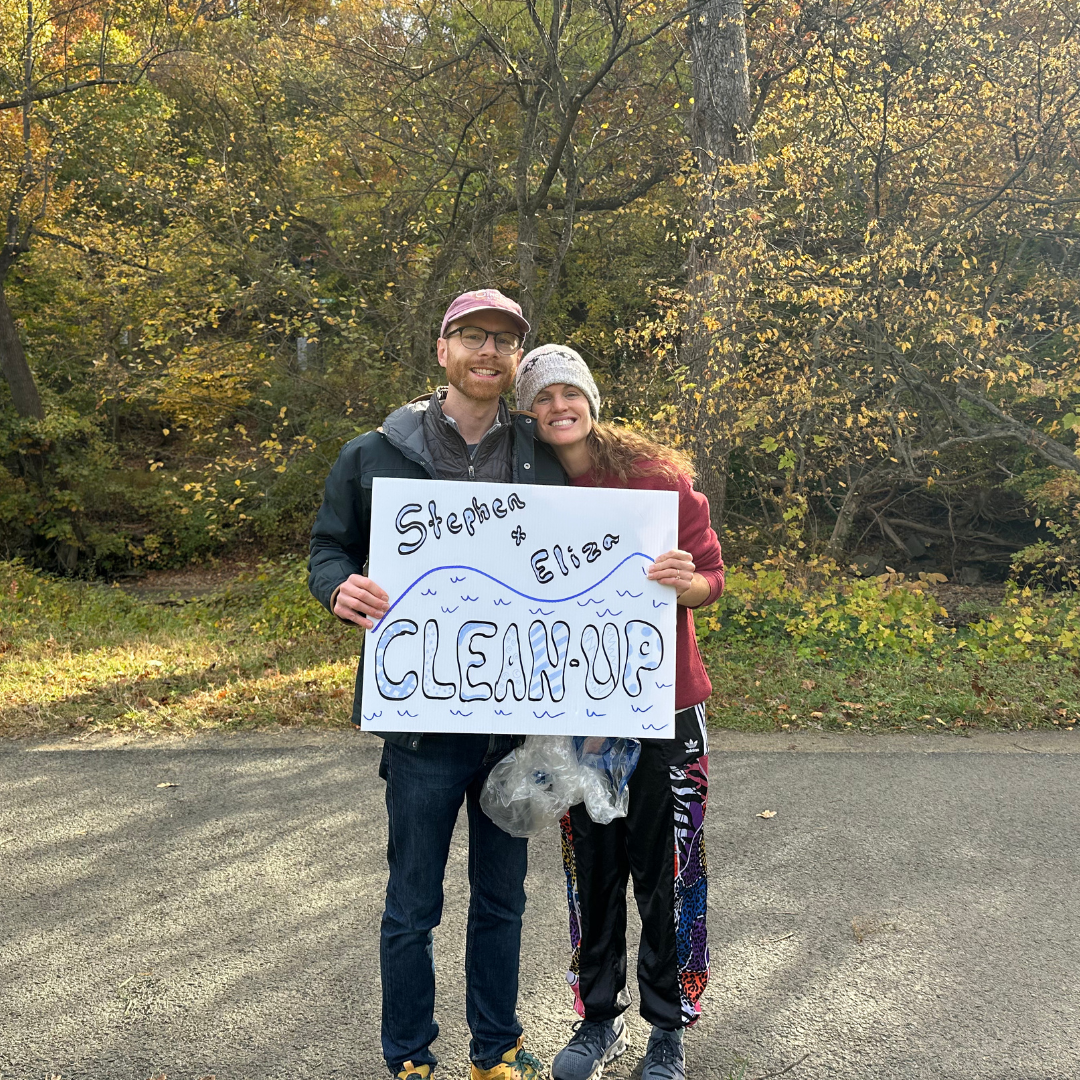

Autumn on nanjemoy. Photo courtesy of gabrielle tayac.

A fundamental ethic in Piscataway philosophy centers on reciprocity. We take care of each other. The land cares for you, you care for Mother Earth. All in balance.

Nanjemoy maintains a healthier ecosystem than many places in the region, its trees oxygenate DC. So we, in turn, have this opportunity to let this space breathe, protect it, help the lost environments and cultures regenerate.

When deforestation was threatened by a solar project (and don’t get me wrong, I support renewables like solar), environmentalists, community folks, and Piscataway activists spoke up. We took action together, perhaps finally all understanding the necessity of indigenous wisdom – now shown through science, that all is connected.

Jansikwe, 17 years old, is a climate justice activist. On September 20, 2019, she spoke clearly at the Youth Climate Strike, to urge adults to take action for the future generations. And the very next day, she took a moment from the fight, to let the Nanjemoy peace restore her and to remind her why her actions matter. Like the tides, always returning.

Guest Author: Dr. Gabrielle Tayac

Gabrielle Tayac, Ph.D. (Piscataway Indian Nation) is a Harvard-trained activist-scholar who served 18 years as a staff historian at the Smithsonian National Museum of the American Indian. Currently, she dedicates her time to research, cultural recovery, and the sweet savoring of time before an empty nest.