The river that shaped my Olympic journey: a reflection on the Potomac

/By Aquil Abdullah, First African-American Male Olympic Rower for Team USA

Paddler enjoying the potomac river in summer

Adapted from Aquil Abdullah’s website’s blog post

Finding My Connection to the Water

Take a moment and imagine your favorite spot on the Potomac River. Picture it vividly—the sounds, the smell, the feeling, the view. Now think about what that place means to you.

Each of us carries a different image of the Potomac River, but we all share in its gifts.

I was born right here in Washington DC. As a kid, I played just about every sport you can imagine—football, track, swimming, hockey, golf, basketball, baseball...and I was just about average in all of them except for football.

But in my senior year of high school, everything changed when I found rowing. A bunch of my friends rowed, and living in Georgetown at the time, I'd see high school and college rowing shells moving gracefully up and down the river. A group of my friends finally convinced me to give the sport a try, and I started out rowing just like every other sport I'd tried: poorly!

But something about the Potomac River called me back day after day. In the early spring of my senior year of high school, I was offered a scholarship to row at The George Washington University, which meant having to decide between football and rowing. Much to the chagrin of my father, who played football in his youth, I chose rowing.

From the Potomac to the Olympics

Aquil Adullah M1x, 2002 Rowing World Championships Seville

Freshman year of college can be daunting, and I had a pretty rocky transition, but rowing and the Potomac River provided a continuity that helped me get back on track and stay afloat. When the pressure of my studies began to feel overwhelming I could lose myself in the rhythmic swing of the boat as we raced down the Potomac, and return to shore with a sense of purpose.

Not long into my college career, I began to believe that I might someday be able to compete in rowing at the international level, and it was long hot summers spent racing athletes from Harvard, Yale, Syracuse, Dartmouth, Georgetown, Brown and the Coast Guard Academy that provided the proving grounds for my aspirations. August on the Potomac River can be a grueling place to train, but on those long humid days as I rowed past the Kennedy Center, as I rowed under Memorial Bridge and as the sound airplanes rattled my teeth as I rowed past Reagan National Airport, I began to believe that there was something special about the river, but I also began to believe that there was something special about me.

In 1996, I became the first African-American to win the US National Championships in the single sculls. I also went on to win The Diamond Challenge Sculls at Henley Royal Regatta, and in 2004, I represented our country in the Double Sculls at the Olympic Games in Athens, Greece.

But my path to the Olympics was filled with detours. In 2000, I lost the Olympic Trials by .33 hundredths of a second. Returning home and rowing on this river, I realized that my journey wasn't over.

This raises an interesting question: What if the Potomac River hadn't been there? Or what if it had been too polluted to row on? Would I have become a rower? Would I have gone to the Olympics?

The Water That Flows Through Us

Returning to the Potomac, with Olympic partner Henry Nuzum

Let me ask you a question: Where does your water come from?

It sounds simple, but how many of us can answer that? I only know because I looked it up—my drinking water comes directly from the Potomac River, via the Washington Aqueduct Treatment Plant.

The same river where I flipped my boat as a novice rower, the same river where I trained for the Olympics—that's the river that flows through my taps, and that's the water that flows through me. I am the Potomac River, and if you live in the D.C. region, you are the Potomac River.

How would we behave differently if we truly understood this connection? If we recognized that the river we boat on, fish in, and admire from scenic overlooks contains the water that sustains us?

Why Conservation Matters

Aquil with Potomac Conservancy President, Hedrick Belin and Board CHair John Froemming

This is why the work of the Potomac Conservancy is so vital. When they protect streamside forests in the headwaters, they're protecting the source of our drinking water.

When they advocate for water protection laws, they're fighting for the river that shaped my life and continues to shape our region.

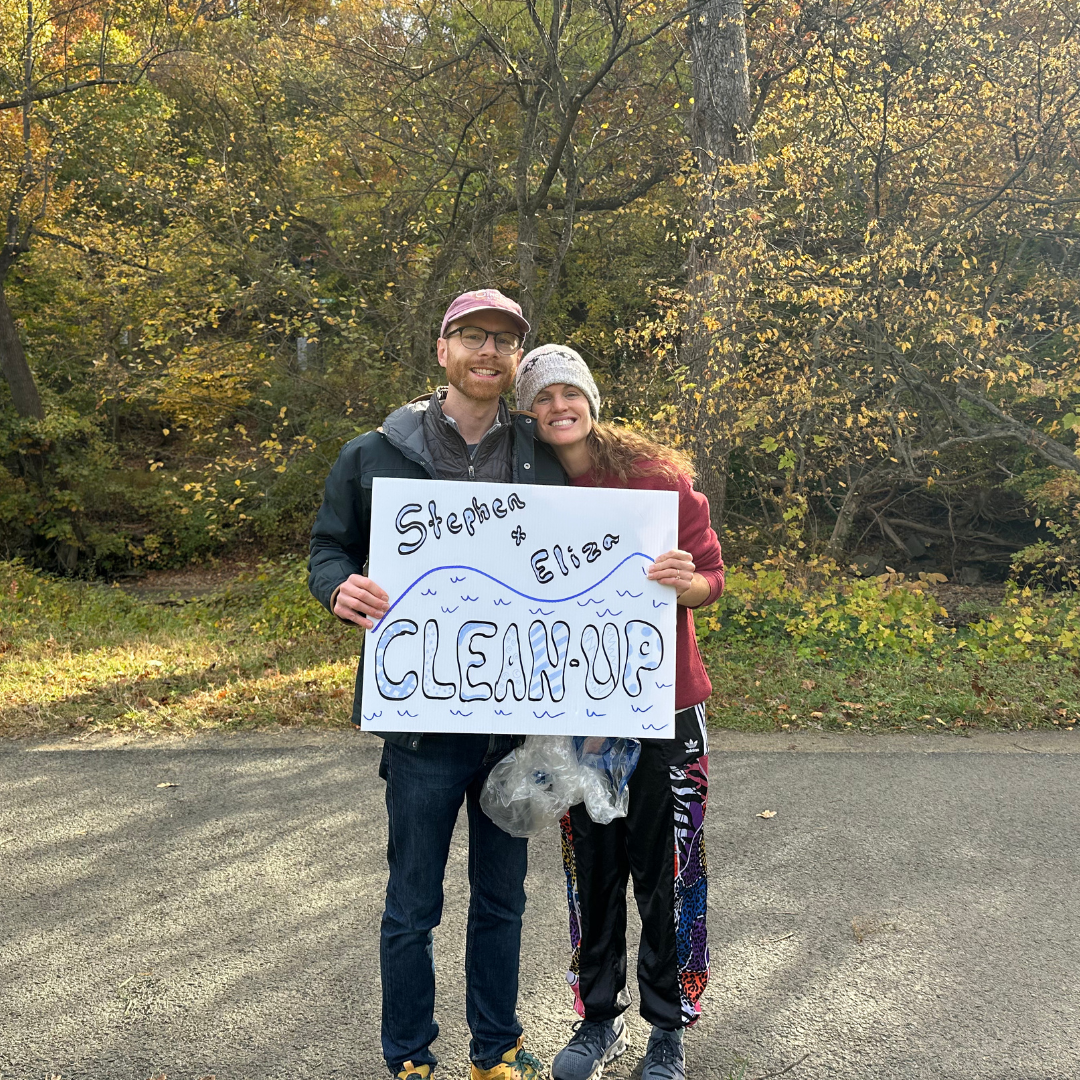

When they mobilize volunteers to restore shorelines, they're ensuring that future generations can form the same meaningful connections to the river that I was fortunate enough to experience.

The Potomac River is the crucible where my rowing mettle was forged. Without that river, my story simply wouldn't exist. And I wonder how many future stories depend on our actions today

Your Relationship with the Potomac

What is your relationship with the Potomac? Is it just scenery on your commute? Is it recreation on the weekend? Or is it, as it was for me, a life-changing force?

Whatever your answer, remember that the river gives to all of us every day.

In closing, I would like to leave you with a Hawaiian phrase that has come to mean a lot to me:

Malama Aina. Malama Kai.

Care for the land. Care for the water.

Aquil Abdullah made history as the first African-American male to represent the United States in rowing at the Olympic Games. Born and raised in Washington D.C., his journey began on the Potomac River, which continues to inspire his advocacy for water conservation and environmental stewardship. This blog post is adapted from a speech delivered at the Take Me To The River Celebration hosted by the Potomac Conservancy.